Congratulations to Han Kang on winning the Nobel Prize for Literature! Praised ‘for her intense poetic prose that confronts historical trauma and exposes the fragility of human life’, it’s encouraging to know that in these times of equality, no-one need be held back by characteristics such gender or lack of writing ability. In honour of the award I’m re-posting my review, from 2018, of her best known work ‘The Vegetarian’…

Until now, the few reviews I’ve done on this blog have been of books, and films, that I’ve liked, the rationale being that if you can’t find something good to say, then don’t say anything. I don’t like to be critical, but sometimes, in the interest of balance, perhaps I should be. This is the time, and The Vegetarian, by Han Kang, is the book.

Warning

This review gives away a lot of the plot so, as they say on the sports reports, if you don’t want to know the result, look away now…

Synopsis

The Vegetarian is the tale of a young woman’s descent into madness, told mostly from the perspective of the people around her. The mental instability begins when she decides she can no longer eat meat, apparently inspired by a nightmare. Eventually she decides she can’t eat at all. The book ends with her close to death, in an ambulance on the way to hospital.

My Analysis

I can at least start with some positives. I can say that I did find the book both interesting and different. I was very aware of what I took to be the differences in attitude and outlook of the characters living in a different culture (I presume this was the reason, rather than it being just that the author had some strange ideas!) I didn’t find the book particularly satisfying, for a number of reasons, the most fundamental of which was that the reasons for the main character, Yeong-Hye, not wanting to eat meat, indeed the reasons for all of her strange behaviour, were never really explained. Perhaps it was just because she was mad, so that there was no reason. All the same, it would have been nice to have had some sort of description of how her mind was working, even if its processes were mixed up and illogical due to the madness. The book left me feeling ‘why? – what was it all about?’

The author’s approach to the male characters is rather skewed and unsympathetic. Yeong-Hye’s husband is portrayed as being very superficial, unfeeling and cruel, with little care for his wife. When she doesn’t respond to his sexual advances he rapes her, not just once, but habitually. And when her madness becomes more pronounced, he is happy to abandon her. Her brother-in-law, a character who we’d been led to believe might be a decent chap, uses her deranged state of mind to persuade her to have sex with him. And we later discover he’s been serially raping his wife, Yeong-Hye’s sister, In-Hye. As if that wasn’t enough, In-Hye later reveals that the girls’ father systematically abused Yeong-Hye when they were children. There’s nothing wrong with having a bad guy, but it seems as though the author wants us to believe that all men are complete bastards. Perhaps she accurately portrays men in South Korean society – I sincerely hope not.

I also had a problem following what was going on. The order of events was often unclear. Often it wasn’t even clear which character was speaking, or acting. The text would read something like, ‘X did this’, followed by ‘she said this’, but the ‘she’ would refer to Y, not X. At other times, names were specified to make clear who was speaking or acting, but in language that was laughably clumsy (Y said this, X said that she, Y, thought that X thought this of Y, whereas X didn’t think she, Y, was what Y said X thought). Maybe it was down to the translation – although the translator has impressive credentials and, if the blurb in the back of the book is to be believed, is highly thought of. I found myself wondering just what part the editor played in the production of this book (or if there even was one.)

As the book progresses, it becomes ever more ‘spiritual’, with descriptions of dreams and fantastical analogies. I don’t have a problem with this, except that it all seemed rather confused. I got the feeling that the author was trying to tell me things – suggesting analogies between the dreams and the real lives of her characters, but was doing it in such a confused way that it just didn’t come across. Hence my feeling that I wasn’t clear what it was all about. One of the last of the dreams was of a black bird flying up into the sky. Was this the author’s way of telling us the main character had died? I had to go back and re-read the passage, and even then I wasn’t sure which of the two women was having this vision. I’d also say that if this was what it meant, I’m afraid it’s a bit of a cliche, so rather a poor ending.

Add to all this that there isn’t a single character in the book that a reader could feel any empathy for, and I’m left wondering just what there is in this book to make it worth reading. I made it to the end – I hate to give up on a book – but it was hard work.

Deborah Levy, writing in the Guardian, called The Vegetarian ‘a modern masterpiece’, and with inevitable insecurity I wondered – is it just me? Am I over critical of other writers’ work? Am I becoming bitter – do I want to put down the work of those who have achieved more literary success than me? Mrs Literarylad, who I trust as an arbiter of literary quality, read the book after me, and her comments made my criticisms seem positively reserved. Despite, like me, not liking to give up on books, she made it to page sixty-one and no further.

Summary

There are some interesting ideas in the book, and it is engaging in places, but ultimately, for the reasons I’ve mentioned, unsatisfying. Bear in mind that this book won the Man Booker international prize in 2016. Is this really the very best writing being done in the world today?

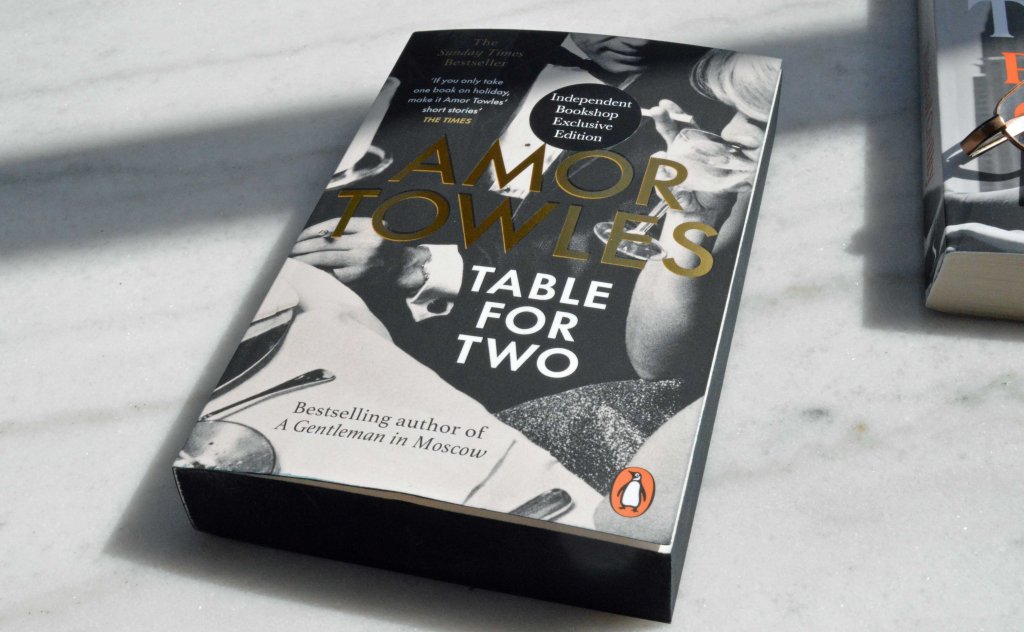

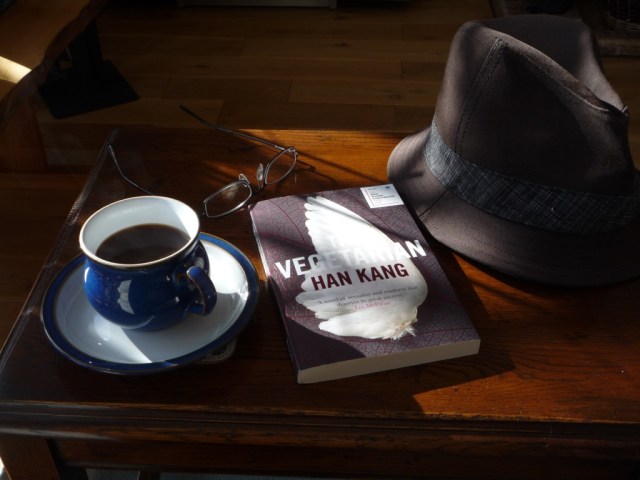

The cover of the book however, is both striking and beautiful, and I think it was this that made it stand out for me, but you know what they say…

Text & original photography copyright Graham Wright 2018